Lieutenant Commander Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre STOKER DSC MiD

Just

before the ANZACs landed at Gallipoli on the morning of 25

April 1915 an Australian submarine, the HMAS AE2

set out on an historic journey. Its mission was to

force a passage up the treacherous Dardanelles Strait into

the Sea of Marmara, and then, in the words of the Chief of

Staff, 'Generally run amok.' Such an

extraordinary order required an extraordinary Captain and

luckily the AE2 had such a Captain, Lieutenant

Commander Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker -- an Irishman. Just

before the ANZACs landed at Gallipoli on the morning of 25

April 1915 an Australian submarine, the HMAS AE2

set out on an historic journey. Its mission was to

force a passage up the treacherous Dardanelles Strait into

the Sea of Marmara, and then, in the words of the Chief of

Staff, 'Generally run amok.' Such an

extraordinary order required an extraordinary Captain and

luckily the AE2 had such a Captain, Lieutenant

Commander Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker -- an Irishman.

Henry Stoker, the second son of a physician, was born in

Dublin on 2 February 1885. At the age of 12 he went to

England to enter a school which specialised in training boys

to pass the entrance examination for the Royal Navy, which

he eventually joined at 15.

His initial service was in the training ship HMS

Britannia, moored in the river near Dartmouth.

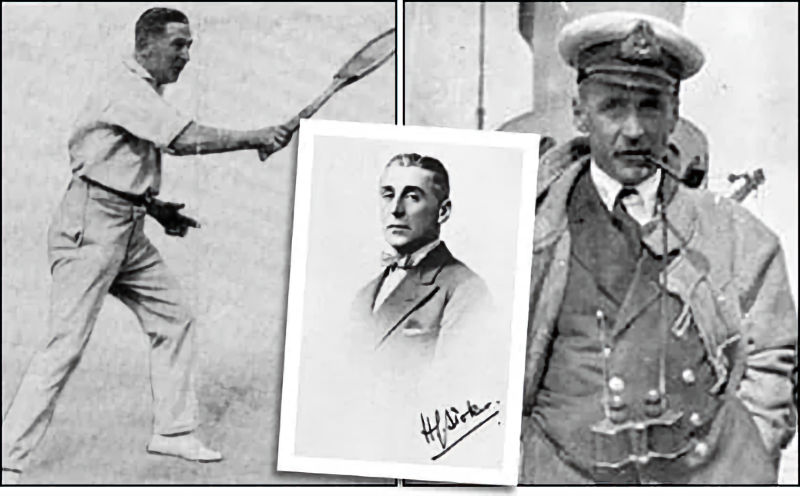

While an average student, he did excel at sport,

particularly rugby and tennis, and he continued to play the

latter well into his seventies. He was promoted to

Midshipman on 30 May 1901 and posted briefly to the

battleship HMS Jupiter, part of the Channel Fleet,

before joining the battleship HMS Implacable which

served in the Mediterranean.

Stoker was promoted to Sub Lieutenant on 30 July 1904, and

left Implacable to undertake courses and

examinations at the Naval College at Greenwich. After

completing his training at Greenwich he was sent to the

armoured cruiser HMS Drake which was operating in

the western Atlantic, off the coast of Canada and the United

States. Stoker became interested in the submarine

service and applied to join this relatively new branch of

the Navy. In October 1906, after a years service in

Drake, he was selected for submarine training and

dispatched to the submarine depot ship HMS Thames

at Portsmouth. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 31

December 1906.

Stoker was very much a free spirit and revelled in the

freedom that the submarine service offered. He

completed his submarine training in October 1907 and in

January 1909 was given command of the submarine HMS A10.

On 19 December 1908, at Exeter, Stoker married Olive Joan

Violet Gwendoline Leacock, daughter of Colonel Schuler

Leacock of the Bengal Cavalry.

In January 1910 he took command of the submarine HMS B8

which, in August 1911, became part of a flotilla of three

submarines based in Gibraltar; these were the first RN

submarines to serve outside of Britain. In 1913 Stoker

volunteered to serve on loan with the RAN as Commanding

Officer of one of the fledgling navy's new submarines.

He was selected, and on 7 November 1913 was loaned to the

RAN as the Commanding Officer of the new submarine HMAS

AE2, one of the two new submarines built at

Barrow-in-Furness for the Australian Navy.

Despite the fact that the rudimentary submarines of that era

had never managed to sail more than 200 miles without

breaking down, the intrepid Stoker and his mixed crew of

Australian and English ratings -- in company with the other

Australian submarine AE1 -- set sail for Australia

on 2 March 1914. On 24 May 1914, after an incredible

voyage of 83 days of which 60 were at sea, the two

submarines made their entrance into Sydney Harbour.

They were the first submarines to travel such a distance.

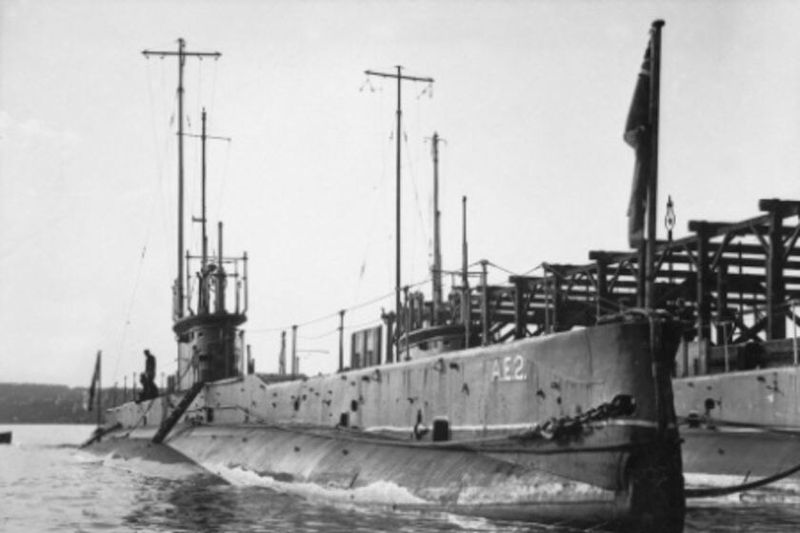

The HMAS 'AE2', in dock in

Sydney, circa 1914. (Australian War Memorial / Sydney Mail)

Soon after their arrival in Australia, the AE1 and

AE2 were sent north to assist in the Australian

occupation of German New Guinea. AE1 was

mysteriously lost with all hands during the mission.

However, Stoker and AE2 successfully returned to

Australia. Immediately on his return, Stoker in his

flamboyant style, bailed up the Australian Defence Minister

-- behind the Speaker's chair in the House of

Representatives -- and talked him into sending the AE2

back to Europe to assist in the European war. Not

content with doing the historic England-Australia voyage

once, Stoker and the AE2 set off back to Europe in

December 1914. However, he only got as far as the

Mediterranean before being ordered to join the British fleet

at Tenedos Island and patrol the entrance to the

Dardanelles. It was the start of the Gallipoli

Campaign.

According to Stoker, in his gripping autobiography "Straws

in the Wind", he quickly...

...'formed the opinion

that an attempt to dive a submarine right through the

Dardanelles Strait and into the Sea of Marmara held

sufficient chance of success to justify the attempt being

made'.

The psychological advantage of entering the Sea of Marmara

and thereby threatening Constantinople from the sea would be

enormous.

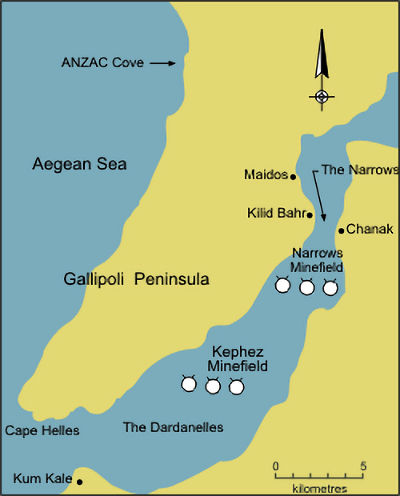

However, the difficulties were tremendous. The Strait

was thirty-five miles long with a continuous current running

at five knots back into the Mediterranean. The whole

area was heavily mined, and although a submarine could dive

under the mines with its periscope submerged it had to

remain at periscope depth in order to navigate the narrow

Strait. If it cleared the minefield, the submarine

would be in narrow waters, completely controlled by the

Turkish Navy.

Despite the fact that the British submarine, the E15,

had just been lost attempting to force the Strait, Stoker

badgered the Admiralty with letters requesting an

opportunity to make an attempt. Finally Stoker was

received by the Chief of Staff, Commodore Roger Keyes and

told he would be permitted to try. Admiral Sir John De

Robeck, the Vice-Admiral of the Mediterranean Fleet told

Stoker that...

...'if you succeed there is no calculating the result it

will cause, and it may well be that you have done more to

finish the war than any other act accomplished'.

As Michael White remarked in his book, "Australian

Submarines"...

... 'these were heady words for any man to have

addressed to him, let alone one such as Stoker who had

already shown outstanding qualities of enterprise and

daring'.

At 2.30 am on the morning of 25 April 1915, Stoker weighed

anchor and set out on the attempt to run the Dardanelles

Strait, which would forever assure him of a place in

Australian naval history. His plan was basically

simple -- travel as far as possible on the surface to

conserve his limited battery power, and dive at daylight or

when he reached the minefields.

The night of 25 April was a beautiful dark and calm night

and the AE2 proceeded along at seven knots in the

centre of the Strait. Suddenly they were spotted by

the searchlight at Kephez and shells began to rain down.

Stoker quickly submerged and passed a harrowing hour slowly

creeping under the minefield. He could hear the

mooring wires of the mines scraping the sides of AE2...

... 'Choose a wrong moment to rise for observation

through the periscope and you choose a moment to hit a mine

-- so choose as few of these moments as possible',

Stoker dryly observed in "Straws in the Wind".'

Rising twice in the minefield, Stoker realised he was

travelling faster than he had anticipated. When he

rose for the third time, he was pleased to find himself

through the minefield and only three hundred yards below the

famous Narrows.

The Turks were now well aware of the AE2's presence

and soon a small Cruiser and a number of Destroyers were

attacking the Submarine. Stoker fired a torpedo which

missed the Cruiser but it struck and damaged one of the

Destroyers. Submerged and trying to escape the

Destroyers' attempts to ram him, Stoker hit the bottom hard

and slid up to a depth of 10 feet, right under the guns of a

shore-based fort. The position was perilous.

AE2 was fast aground with almost half of its structure

out of the water. Stoker described it...

...'as unpleasant as it well could be'.

Luckily they were so close to the fort that the guns could

not be depressed enough to hit the Submarine and after a

short time the efforts of the crew to refloat AE2

were successful. One of the crew recorded in his

diary...

...During all this the Captain remained extremely cool,

for all depended on him at this stage. It is due to

his coolness that I am now writing this account.

Nobody knows what a terrible strain it is on the nerves to

undergo anything like this, especially the Captain, as all

depends on him.

Stoker and his crew resumed their journey pursued by dozens

of Turkish warships. Anti-submarine warfare was in its

infancy and the only way the Turks could attack the AE2

was by trying to ram her. As long as AE2

could stay submerged, it was relatively safe. However

navigating the narrow strait was impossible without

frequently coming up to periscope depth to take a sighting.

Whenever they lifted the periscope, the Turkish ships

attempted to ram. Stoker decided to run the AE2

on to an underwater bank and sit on the bottom until dark.

For sixteen hours the dauntless Stoker and his crew sat in

darkness and silence at a depth of 80 feet. When they

finally rose to the surface they found themselves about half

a mile from the shore in a bay above Nagara Point -- the

worst of their journey was now behind them. Stoker

sent a radio message back to the fleet but never received an

answer, and consequently was unsure if the message had been

received. He was to learn much later that the message

was indeed received, and that his message was to change the

course of history.

The Allied landings on the Gallipoli peninsular had been met

with fierce resistance. From their position on the

beach General Bridges and his staff were alarmed at the

ANZACs position and requested that they be withdrawn back to

the fleet. Just as Stoker's message was received, a

midnight conference was being held on the flagship HMS

Queen Elizabeth to decide whether to withdraw the

troops off the peninsular.

A friend of Stoker's, Lieutenant Commander C G Brodie,

ignored requests to keep quiet and read to the conference

Stoker's message heralding AE2's success.

'The psychological impact at that precise time was

momentous', Michael White said in Australian

Submarines.

It will never be known if they were actually going to pull

the troops off Gallipoli, but after Stoker's message was

read Hamilton sent his famous 'dig, dig, dig' message to the

Australians:

Your news is indeed serious. But there is nothing

for it but to dig yourselves right in and stick it out.

It would take at least two days to re-embark you, as Admiral

Thursby will explain to you. Meanwhile the Australian

submarine has got up through the Narrows and has torpedoed a

gunboat at Chanak.

P.S... You have got through the difficult business.

Now you have only to dig, dig, dig, until you are safe.

The news of the AE2's achievement spread to the

Diggers clinging to the Gallipoli cliffs and lifted their

morale. A notice was stuck on a shell-shattered stump

on the hillside:

'Australian sub AE2 just through the Dardanelles.

Advance Australia'.

Meanwhile Stoker was pressing on in AE2 towards the

Sea of Marmara. He encountered two Turkish warships

and fired a torpedo at the largest but was unsuccessful.

After spending the night of 25-26 April on the surface,

AE2 finally entered the Sea of Marmara early in the

morning of 26 April. Their mission now was to prevent

Turkish ships transporting troops across the Marmara to

Gallipoli.

Spotting a likely target Stoker fired one of his precious

torpedoes but again missed. He spent the remainder of

the day on the surface sailing among fishing boats and doing

all he could to broadcast the arrival of an allied submarine

in the Marmara. After dark, Stoker again attempted to

contact the fleet by wireless but was forced to dive

constantly to escape Turkish patrol vessels.

At dawn Stoker resumed the offensive and fired a torpedo at

a ship which was accompanied by two destroyers. The

torpedo's engine failed to start and Stoker just managed to

avoid being rammed by one of the destroyers. No other

ships were sighted for the rest of the day which shows that

the AE2's presence was curtailing Turkish ship

movements.

By the morning of the 29th, Stoker was still sailing in the

Sea of Marmara and harassing any Turkish ship he could find.

However, he was now down to one torpedo which he decided to

keep in reserve. His plan was to sail around, be as

provocative as possible, and try to fool the Turks into

believing that more than one submarine had made it to the

Sea.

Early on the evening of the 29th, while sailing towards

Marmara Island, the crew of AE2 was surprised to

encounter another submarine. It was the British

submarine E14 under the command of Captain Boyle,

which had been dispatched after the Admiralty heard of

Stoker's successful passage up the Strait. Boyle asked

Stoker what he planned to do the next day. It had been

Stoker's intention to sail to Constantinople but Boyle,

being the senior officer, overruled that plan and arranged

to rendezvous with Stoker the next morning. This

decision would seal the fate of AE2 and her gallant

crew.

When Stoker surfaced at the rendezvous at 10am, he observed

a torpedo boat and immediately dived. For some

unaccountable reason the AE2 suddenly went out of

control and began rapidly to rise. The submarine shot

to the surface about 100 yards from the torpedo boat which

opened fire. Stoker again attempted to dive but the

AE2 was out of control and began to plunge into the

depths.

Stoker took the prescribed emergency action and arrested the

descent, but now AE2 rushed back towards the

surface where it was hit by shells from the attacking boat

and was holed in several places. AE2 was

doomed. Stoker ordered the submarine scuttled and

concentrated on saving the lives of his men.

All the crew survived and were taken prisoner, and together

with Stoker spent the next three-and-a-half years as

'guests' of the Turks. Stoker escaped twice but was

recaptured and endured numerous hardships in Turkish

prisons.

After repatriation he was awarded the Distinguished Service

Order (London Gazette, 22 April 1919)

‘In recognition of his gallantry in making the passage

of the Dardanelles in command of HM Australian Submarine AE2

on 25 April 1915’.

Six months later he was mentioned in dispatches (London

Gazette, 17 October 1919)

‘For valuable services in HM Australian Submarine AE2 in

the prosecution of the war’.

He was offered the command of a Cruiser but chose to leave

the Navy for a career on the stage. He was also having

serious problems in his personal life and divorced his wife

in early 1919 and lost contact with his two daughters.

He appeared in a number of plays, films and television

dramas. His contemporaries included Sir Laurence

Olivier and Sir John Mills.

When the Second World War began, Stoker was recalled to

duty, commanded a naval base, worked in public relations,

and was involved in the planning for D-Day.

Man for all seasons: Henry Stoker commanded

the AE2, played at Wimbledon and acted in the West End

In 1948 he enjoyed what he described as “one of the most

pleasant days I ever spent in my life” as a guest of King

George VI. While playing cricket he was in at bat and

facing the King’s bowling. He said, “Sir, please

remember that I was a shipmate with your grandfather”,

raising a laugh all round.

The larger-than-life Stoker died on his 81st birthday, the

2nd February 1966.

While Australia takes justifiable pride in the heroism of

the ANZACs, and Simpson and his donkey are part of the

nation's folklore, little is known of the dauntless Henry

Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker. Yet this man sailed a

submarine around the world, and pulled off one of the most

daring exploits in naval history. His achievements

deserve to be placed firmly in history; he caused the Turks

to abandon attempts to reinforce Gallipoli by sea, and

forced them to use a much more hazardous land route.

His success changed the whole course of the Gallipoli

Campaign. As searchers have now successfully located

the sunken hull of AE2, it's time that the intrepid

Stoker and his crew were awarded their place in Australian

history.

Lieutenant Commander Stoker's

medal group, now on display in the Naval Heritage Collection

in Sydney

Sources:

Anzac Day Commemoration Committee

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Australian War Memorial

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)

The UK Telegraph

Compiled by Laurie Pegler

|