Navy Victoria

Network

Proudly supported by the Melbourne Naval Committee

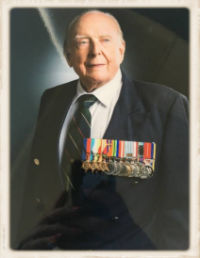

Captain John Philip Stevenson AM RAN

John Philip Stevenson was born in Melbourne on 24 August 1921,

the son of Rear Admiral John Bryan Stevenson, RAN, and Olive Brooke

Stevenson (née Bailey). He entered the Royal Australian Navy (RAN),

in 1934, as a 13-year old Cadet Midshipman and underwent training at

the RAN College at HMAS Cerberus. There he attained his sporting

colours for tennis and at passing out was awarded the prize for

mathematics-physics-chemistry.

John Philip Stevenson was born in Melbourne on 24 August 1921,

the son of Rear Admiral John Bryan Stevenson, RAN, and Olive Brooke

Stevenson (née Bailey). He entered the Royal Australian Navy (RAN),

in 1934, as a 13-year old Cadet Midshipman and underwent training at

the RAN College at HMAS Cerberus. There he attained his sporting

colours for tennis and at passing out was awarded the prize for

mathematics-physics-chemistry.

Upon graduation he became a Midshipman, on 1 January 1939, and joined his first ship, the heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra (I), on 26 January. He travelled to the United Kingdom in May 1939 for service on loan with the Royal Navy (RN) and joined the County Class heavy cruiser, HMS Shropshire. He was serving in her, in the Mediterranean, when war broke out in September 1939. Shropshire was ordered to take up patrol in the South Atlantic and, in 1940, conducted patrol and escort duties in the Indian Ocean between Cape Town, Durban, Mombasa and Aden.

Stevenson left Shropshire on 1 September 1940 to undertake courses ashore in the United Kingdom at which time he was promoted Acting Sub Lieutenant and he was confirmed in the rank on 1 January 1941. Portsmouth was experiencing heavy bombing at that time and every second night Sub Lieutenant Stevenson was required to take charge of a 12-pounder anti-aircraft gun and its crew. He returned to RAN service when he joined the commissioning crew of the N Class destroyer HMAS Nestor on 3 February 1941. Nestor joined the Home Fleet, based at Scapa Flow, and spent her first months of service in the North Atlantic on escort, patrol and screening duties. She was involved in the hunt for the German battleship Bismarck, but was in Iceland refueling when Bismarck was sunk on 27 May 1941.

Cadet Stevenson (front row left) with his class at Flinders

Naval Depot, 1937.

From July 1941 Nestor performed escort duties in the Mediterranean and South Atlantic, and on 15 December was credited with sinking the German submarine U-127 off Cape St Vincent. She operated in the Indian Ocean between January-June 1942 as a unit of the Eastern Fleet before returning to the Mediterranean theatre. It was during that time, on 1 April 1942, that Stevenson was promoted to Lieutenant. On 15 June, while acting as one of the escorts for a large convoy bound for Malta, Nestor was straddled by two bombs which caused severe damage and killed the four sailors occupying No 1 Boiler Room. HMS Javelin attempted to take her in tow but she was scuttled early the following morning after Javelin had embarked her survivors including a concussed Lieutenant Stevenson.

Following the loss of Nestor, Lieutenant Stevenson joined her sister ship HMAS Napier, which conducted escort and patrol duties in the Indian Ocean in late 1942, before returning to the UK to rejoin the now HMAS Shropshire on 25 June 1943. Shropshire had been commissioned as an RAN vessel in April 1943 and she subsequently joined the Australian Squadron in Brisbane in October. She participated in operations in New Guinea and the Netherlands East Indies before Lieutenant Stevenson left the ship to undergo radar training at HMAS Rushcutter and in the United Kingdom. After a journey that took him across the Pacific Ocean, the continental USA and the Atlantic Ocean, he and his travelling companion, Lieutenant Robin ‘Dusty’ Millar, arrived in London in June 1944 to be told by the Admiralty’s Director of Scientific Research that they did not have the requisite level of education to undertake the training. They were saved by the determination of Lieutenant Millar who, in Stevenson words:

...protested very strongly and said to this scientist that there was no way we had come all that way to be told we couldn’t do the training that our government was aiming for and he said ‘well, put us down there and if we can’t do the job then get rid of us, but give us a go first.'

After six months of training, Lieutenant Stevenson topped the course with Lieutenant Millar just a couple of places behind him.

Lieutenant Stevenson was appointed the RAN Fleet Radar Officer while Lieutenant Millar was appointed the Radar Training Officer. As Stevenson’s presence in Australia was more urgent, he was to return home by air while Millar returned by sea. So began another epic journey for Stevenson as he changed aircraft multiple times and endured numerous enforced layovers. By the time he returned to Sydney many weeks later, he found Lieutenant Millar was already there.

Lieutenant Stevenson returned to Shropshire, then in New Guinea waters, in April 1945 and remained with the ship for the rest of the war. Shropshire was present in Tokyo Bay stationed some 700-800 yards from USS Missouri during the Japanese surrender. Immediately following the surrender Stevenson was assigned to a team of Australians, Americans and Canadians on prisoner of war (POW) recovery duties around Nagasaki. There he saw first-hand the devastating effects of the atomic bomb which had been detonated less than two weeks earlier. His wartime diary describes what he saw as the aircraft in which he was travelling approached the city:

God what a mess. A stirred up desert. The hills overlooking the town have all been scorched black. Quite a harbour with lots of ships. One on dock. Could see that all the large ships were sitting on the bottom. 50% of the town looks completely destroyed, another 20% shattered. No smoke from the chimneys, no sign of life. A few small boats underway. Must have been a lovely harbour once.

He was also struck by the appalling condition of the Allied POWs:

...the next stop went on north...where the coalmines were and where many, many prisoners of war were employed working down the mines, and what a horrible sight they were, all on the level of starvation and sickness and death and all the rest of it...they were in desperately bad shape; many, many were just about to die and did die. Many just surviving and so utterly thrilled to see us with lots of weeping and wailing and happiness. We managed to get an airdrop in while we were there, which was tremendous and with great relief there was cigarettes and chocolate and basic foodstuffs and medicine and so on.

He supervised the clearing of wharves to allow for the landing of

the occupying Allied forces before making assessments of the POW

camps in the area, organised the delivery of emergency supplies and

finally the repatriation of POWs. After nearly two weeks in

Nagasaki, he returned to Shropshire in Tokyo for return to

Australia.

He supervised the clearing of wharves to allow for the landing of

the occupying Allied forces before making assessments of the POW

camps in the area, organised the delivery of emergency supplies and

finally the repatriation of POWs. After nearly two weeks in

Nagasaki, he returned to Shropshire in Tokyo for return to

Australia.

Upon his return, Lieutenant Stevenson was posted to HMAS Watson taking over the position of Radar Training Officer from his friend Lieutenant Millar. In November 1946 he departed for the United Kingdom and a four-year loan period with the Royal Navy where he underwent courses in navigation and fighter direction. He later served in the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean, and saw operational service in the early days of the Malayan Emergency.

Stevenson was promoted to Lieutenant Commander in April 1950 and returned to RAN service that July when he joined the carrier HMAS Sydney (III) which was then embarking her second carrier air group in Portsmouth. Upon his arrival in Australia, he was given his first command; the frigate HMAS Barcoo which recommissioned as a training ship in March 1951. He briefly commanded HMAS Hawkesbury (I) when the River Class frigate recommissioned in May 1952 and then joined HMAS Australia (II) as the ship’s navigation officer, and later re-joined Sydney as the Fleet Navigation Officer.

Aboard Sydney, Lieutenant Commander Stevenson visited the United Kingdom for the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II where he commanded the RAN detachment taking part in the coronation parade. Sydney returned to Australia via the USA and New Zealand, following which she conducted a post-armistice patrol in Korean waters. It was during this time, on 30 June 1954, that Stevenson was promoted to Commander.

In 1954 Commander Stevenson was appointed Director of Plans which saw him based in Navy Office (Melbourne) and later at Manus Island in New Guinea. At the conclusion of this posting he embarked in HMY Britannia, at that time in Malayan waters, as the naval equerry to His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh who was to visit Australia for the opening of the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne.

He was Commanding Officer of HMAS Anzac (II) from January 1957 to June 1958 during which time the Battle Class destroyer served in the Far East Strategic Reserve (FESR) and spent some ten months in Asian waters. In July 1958 he was selected to attend the Naval Command Course at the US Naval War College in Rhode Island, USA, followed by the US Naval Tactical Course in Virginia during July-August 1959. However he was recalled to Australia in early May 1959 to take up the position of Defence attaché to Thailand at a time when communist activity in the country was high. He was promoted Acting Captain on 1 July 1959 and confirmed in that rank on 31 December 1960.

Upon his return to Australia, Captain Stevenson assumed command

of HMAS Watson in October 1961, and the following October returned

to sea in command of HMAS Vendetta (II) as well as assuming the

position of Captain (D) 10th Destroyer Squadron. He was appointed

honorary Aide-de-camp to His Excellency the Governor-General on 8

December 1961. In 1963 Captain Stevenson served for the second time

in the FESR, on this occasion in command of Vendetta.

Upon his return to Australia, Captain Stevenson assumed command

of HMAS Watson in October 1961, and the following October returned

to sea in command of HMAS Vendetta (II) as well as assuming the

position of Captain (D) 10th Destroyer Squadron. He was appointed

honorary Aide-de-camp to His Excellency the Governor-General on 8

December 1961. In 1963 Captain Stevenson served for the second time

in the FESR, on this occasion in command of Vendetta.

On 10 February 1964, the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne (II) collided with the destroyer HMAS Voyager (II) resulting in the loss of 82 lives, all from Voyager. Captain Stevenson sat on the Board of Inquiry into the loss of Voyager, an unfortunate irony considering the tragedy that was to befall Stevenson while commanding Melbourne five years later.

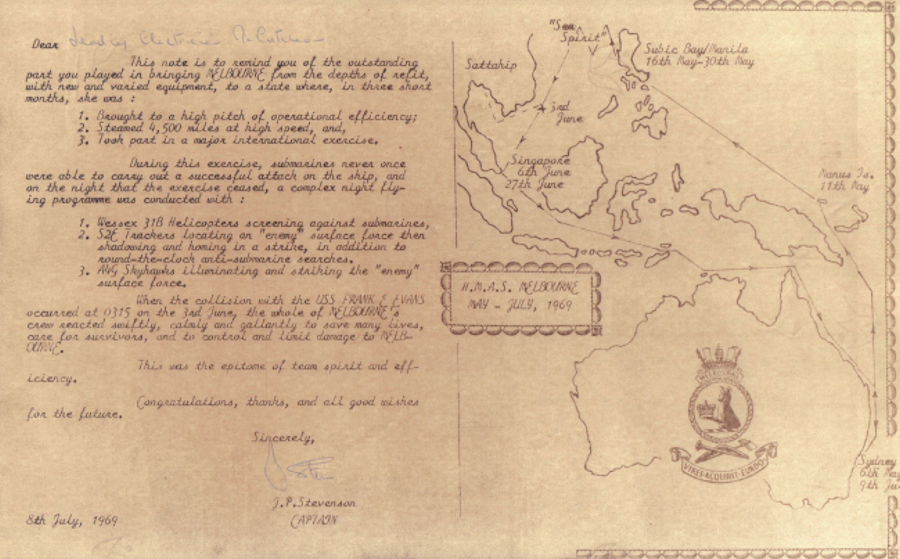

He assumed temporary command of the recently converted fast troop transport HMAS Sydney (III) that April, which carried Australian troops to Borneo later in the year. In 1965 he took command of HMAS Cerberus and was also appointed Naval Officer in Command - Victoria. At the end of 1966 he took passage to the USA to take up the position of naval attaché in Washington. He returned to Australia in mid-1968 and on 8 October, assumed command of HMAS Melbourne (II) which was undergoing a major refit at Garden Island.

Melbourne commenced work-ups in February 1969 and sailed from Sydney for Southeast Asia on 5 May 1969 with 805, 816 and 817 Squadrons embarked. In the early hours of 3 June 1969 in the South China Sea, during the SEATO Exercise SEA SPIRIT, the American destroyer USS Frank E Evans cut across Melbourne's bow and was cut in two in an incident all too similar to that of Voyager (II) five years earlier. The forward section of Evans sank with the loss of 74 lives and Melbourne sustained extensive damage to her bow section.

A joint USN/RAN Board of Inquiry into the tragedy held Captain Stevenson partly responsible stating that, as Commanding Officer of Melbourne, he could have done more to prevent the collision from occurring; however, a subsequent RAN court-martial cleared him of any responsibility.

The integrity of the initial Board of Inquiry has since been questioned, particularly as it was presided over by Rear Admiral Jerome King, USN, the officer in overall tactical command of Evans at the time of the collision. Stevenson’s defence council, Gordon Samuels, QC, later Governor of New South Wales, said that he had “never seen a prosecution case so bereft of any possible proof of guilt.”

Before leaving HMAS Melbourne CAPT Stevenson wrote to every

member of his ship’s company, thanking them for their Service.

Captain Stevenson subsequently resigned from the RAN bringing to an end what had been, up to that point, a distinguished 35-year naval career. He went on to enjoy a successful career working for the Australian Gas Light (AGL) from 1970-1985 after that he was tasked with setting up ELGas from 1985-1987. He then retired and spent time skiing in Lake Tahoe before moving to Burradoo with his wife, Joanne in 2000. They were married for 54 years when she died in 2012.

The story of his experience of the Melbourne/Evans tragedy was told by his wife, Joanne, in the books ‘No Case to Answer’ (1971) and ‘In the Wake’ (1999).

Captain Stevenson appearing at his court martial at Balmoral

with his wife, Joanne.

The court martial found that Captain Stevenson had 'no case to

answer'.

Apology

In December 2012, Stevenson received an official apology from the Minister for Defence, the Hon Stephen Smith, MP, in which he states that Stevenson was not treated fairly by the government of the day and the Australian Navy following the events of 1969, and describes Stevenson as ‘a distinguished naval officer who served his country with honour in peace and war’.

ABC 7:30 Report: Official

apology for HMAS Melbourne Captain

and interview with Captain Stevenson 07 February 2013

ABC PM report: Captain Stevenson interviewed by Peter

Lloyd on 6 December 2012.

Australia Day Honours

Captain Stevenson was appointed as a Member

of the Order of Australia (AM) in the 2018 Australia Day Honours

List 'for significant service to naval veterans through a range of

roles'. His daughter, Kerry Stevenson, said that while

her father was now vision impaired he was still “bright as a

button”.

“He is delighted to be receiving an AM and he is really moved by

this recognition as are many others who know him and the service he

gave to this country,” she said.

Vale

Captain John Philip Stevenson AM RAN, died in Sydney on 30 January 2019 and was farewelled with a full naval funeral at Garden Island Naval Chapel, Sydney on 15 February 2019.

Among Captain Stevenson’s final wishes was for his ashes to be scattered near Gabo Island, off the coast of eastern Victoria, where he’d scattered the ashes of his father - Rear Admiral John Bryan Stevenson.

A ceremony was conducted on Melbourne’s flight deck while the ship was in transit to Hobart, and was attended by the late Captain’s children: Bryan and Kerry Stevenson and Henry Innis.

Melbourne’s Commanding Officer, Commander Marcus Buttler, also attended Captain Stevenson’s funeral at Garden Island in Sydney earlier in the year, and said it was fitting to pay strong tribute to his legacy.

“It’s always an honour and a privilege to celebrate the life and service of such a significant member in the history of both Melbourne and the Royal Australian Navy,” Commander Buttler said.

“The crew and I are always grateful for the opportunity to continue the story of HMAS Melbourne, and build on the legacy left by great Australians such as Captain Stevenson,” he said.

Click on the image below to view images of his funeral and the scattering of his ashes at sea.

Sources:

Royal

Australian Navy

Navy Daily

ABC - PM

ABC - 7:30

The Southern Highland News

Sydney Morning Herald