Navy Victoria

Network

Proudly supported by the Melbourne Naval Committee

LCDR Leonard 'Leon' Verdi Goldsworthy GC DSC GM RANVR

Leonard Verdi Goldsworthy (1909–1994), naval officer and factory manager, was born on 19 January 1909 at Broken Hill, New South Wales, second son of South Australian-born parents Alfred Thomas Goldsworthy, miner, and his wife Eva Jane, née Riggs. Known widely as ‘Goldy’ or ‘Ficky’ (a derivative of ‘Mr Fixit’), Leon spent his early years in South Australia. After leaving Kapunda High School, in 1924 he became a junior apprentice in the physics workshop at the University of Adelaide. Over the next several years he took part-time courses in physics, chemistry, mathematics, electrical engineering, sheet metal work, and French polishing at the South Australian School of Mines and Industries. Quiet, short of stature, and of wiry build, he kept himself fit

by wrestling and gymnastics. He moved to Western Australia in

1929 and obtained employment in an electrical business in Perth.

On 4 November 1939 at St George’s Cathedral, he married Maud Edna

Rutherford (d. 1959). Soon after the outbreak of World War II Goldsworthy applied to join the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) but was rejected for failing to meet the required physical standards. His records show he was 5ft 5ins and he was missing the small toes on his left and right feet. Undeterred, he reapplied through the Yachtsmen Scheme, and was appointed as a probationary sub-lieutenant, Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve, on 24 March 1941. The Yachtsmen Scheme - The

Scheme was for yachtsmen to serve with the Royal Navy for a period

of two years. Those under 30 were to join as ordinary seamen

when a file, known as a white paper, was started on them and after

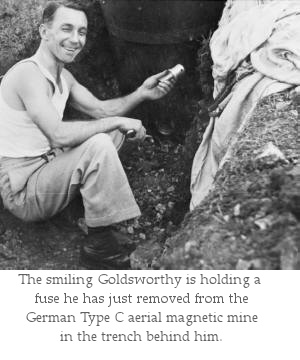

Perhaps the most famous and certainly the most highly decorated group of Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers and other members of the RAN were those brave men engaged in what was known as 'Rendering Mines Safe' or RMS. It was not work that many volunteered for because it took place in solitude, always in uncomfortable circumstances, and often with the nearest human being a good 400 metres away behind a heavy wall or other protective barrier. Defusing German mines was not a job for the faint hearted, and it called for supreme self-confidence and an inquiring mind. In fact, there were never more than a few dozen RMS officers and a surprisingly high proportion were Australian. The British government had decided that rendering mines safe did not fall within the ambit of the criterion 'in the face of the enemy', although when crouched over a German firing mechanism which was designed to blow one to pieces on a dark, cold night in the middle of a destroyed city, it must have seemed so to the practitioners. The outcome was that RMS officers could only qualify for 'civilian' awards, the highest of which was the George Cross - the Victoria cross equivalent. Some measure of the collective achievements of this group of Australian officers to the war effort is their collective total of four George Crosses (GC) and ten George Medals (GM), with many other awards for gallantry. Importantly, like the VC, these decorations could be awarded posthumously. In May Goldsworthy went to Britain for further training, and volunteered to become a rendering mines safe (RMS) officer. In August he joined the Admiralty Mine Disposal Section based in London. During his time there he rendered safe 19 mines and qualified as a diver. In January 1943 he transferred to the Enemy Mining Section at HMS Vernon, the Royal Navy’s torpedo and mine countermeasures establishment at Portsmouth. Goldsworthy’s pre-war technical training and capacity for patience served him well in his new role, and he displayed great skill in defusing explosives on land and underwater. His work often had to be completed in a bulky diving suit, with touch being the only sensory perception available, making defusing enemy mines highly dangerous work. On 13 August 1943 he defused a German mine in the waters off Sheerness, using a special diving suit that he and a colleague, Lieutenant John Mould, had helped develop. Mould went on to form and train Port Clearance Parties ('P' Parties) to clear liberated harbours in Europe. Goldsworthy volunteered to assist but was retained at Vernon for further underwater mine disposal duties. Later that year he defused two particularly tricky influence mines (mines that detonated by the influence of passing vessels), one of which had rested at a Southampton wharf for two years. He was awarded the George Medal ‘… for gallantry and undaunted

devotion to duty’ (London Gazette, April 1944, 1775). The same

month, Goldsworthy disarmed an The George Cross The George Cross (GC) is awarded to those who have displayed the greatest heroism or the most conspicuous courage whilst in extreme danger. It is awarded both to civilians and to military personnel for non-operational gallantry or for gallantry not in the presence of the enemy. The George Cross is equal in stature in the UK honours system to the Victoria Cross and this has always been the case since the introduction of the award in 1940. Goldsworthy was involved in the selection and training of men for port clearance prior to the Normandy (D–Day) invasion in June 1944. Shortly after the Allied invasion of France, Goldsworthy, based in Esmeralda from the Mine Recovery Flotilla, joined the P Parties to undertake mine disposal, underwater demolition and other diving tasks off the Normandy coast. He rendered safe the first type K mine in Cherbourg Harbour in fifty feet (15 m) of water while under enemy shell-fire, and three ground mines on the British assault area beaches. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for ‘for gallantry and distinguished services in the work of mine-clearance in the face of the enemy’ (London Gazette, 16 January 1945, 419). Goldsworthy and another Australian officer, GJ Cliff, RANVR, were both promoted Acting Lieutenant Commanders in September 1944. In October 1944, the Admiralty sent them to the Pacific as British Naval Liaison and Intelligence Officers. There they were attached to the US Navy's Mobile Explosive Investigation Unit No 1, initially in the South West Pacific and subsequently in the Philippines. Their task was to obtain intelligence on US search, recovery and disposal techniques and to forward samples of enemy ordnance material, particularly mines and torpedoes to the UK. Goldsworthy returned to the UK in August 1945 to close down the P Parties and in December he was appointed to the British Naval Technical Mission to Japan where he assisted in compiling a report on Japanese underwater weapons. He returned to Australia in HMS Formidable in April 1946. By his example and courage Goldsworthy was a great inspiration to his team of sea divers who worked with him on these dangerous assignments. The constant depth charging and shelling increased the hazard of his occupation - if any explosion occurred within a mile of him he was likely to be fatally affected by the compression effects of water. He was also a great inspiration to his family.

For a man initially rejected as being physically unfit for the Navy, he finished the war as the Australia's most highly decorated naval officer of World War II, the acknowledged underwater mine disposal expert in Europe, the conqueror of over one hundred weapons in European waters and about thirty in the Pacific. Demobilised on 24 May 1946, Goldsworthy returned to Perth and resumed his employment with Rainbow Neon Light. He rose to factory manager before retiring in 1974. In 1953 he briefly returned to service to take part in Queen Elizabeth’s coronation celebrations in London, and then again in 1957 for a Special Examination Service Officers’ Course. On 13 December 1968 in Perth he married Georgette Roberta Johnston. He became vice-chairman (overseas) of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association in 1991 and was patron of the Underwater Explorers Club of Western Australia.  The Australian War Memorial, Canberra, holds his portrait by Harold Abbott.

Survived by his wife and the daughter of his first marriage, Goldsworthy died of heart disease on 7 August 1994 at South Perth and, following a naval funeral, was cremated and his ashes scattered at sea. In 1995 Australia Post released a stamp bearing his image as part

of the ‘Australia Remembers’ series commemorating the fiftieth

anniversary of the end of World War II. ANZAC Day - 25 April 1989

|

some months of sea service they would be given the chance to get

their commission. Men over 30 who could produce a Yacht

Master’s Certificate went straight in as acting temporary

probationary sub-lieutenants.

some months of sea service they would be given the chance to get

their commission. Men over 30 who could produce a Yacht

Master’s Certificate went straight in as acting temporary

probationary sub-lieutenants. acoustic mine that had lain in the

water off Milford Haven since 1941. At the beginning of this

operation he came to the surface under the boat’s diving ladder,

which pierced his helmet, flooding his diving suit. Extricated by

the prompt action of his assistant, he resumed work with little

delay. In August he was mentioned in despatches '...for

great courage and undaunted devotion to duty', and in the following

month was awarded the George Cross '...for great gallantry and

undaunted devotion to duty’ (London Gazette, September 1944, 4333),

for his work in recovering and defusing mines between June 1943

and September 1944.

acoustic mine that had lain in the

water off Milford Haven since 1941. At the beginning of this

operation he came to the surface under the boat’s diving ladder,

which pierced his helmet, flooding his diving suit. Extricated by

the prompt action of his assistant, he resumed work with little

delay. In August he was mentioned in despatches '...for

great courage and undaunted devotion to duty', and in the following

month was awarded the George Cross '...for great gallantry and

undaunted devotion to duty’ (London Gazette, September 1944, 4333),

for his work in recovering and defusing mines between June 1943

and September 1944.

A

ward at Perth’s Hollywood Private Hospital is named in his honour,

as is a road on Garden Island, where the RAN’s primary naval base on

the west coast, HMAS Stirling, is located.

A

ward at Perth’s Hollywood Private Hospital is named in his honour,

as is a road on Garden Island, where the RAN’s primary naval base on

the west coast, HMAS Stirling, is located.  There

are times - like today - when Leon "Goldy" Goldsworthy remembers the

years he was a mere heartbeat away from death. Australia's

most highly decorated ex-naval man will also recall his mates as he

leads his fellow servicemen along St. George's Terrace on the ANZAC

Day march. "I look forward to the annual reunion, of meeting

old friends, and seeing who is left," he said. "I might not be

able to make it next year."

There

are times - like today - when Leon "Goldy" Goldsworthy remembers the

years he was a mere heartbeat away from death. Australia's

most highly decorated ex-naval man will also recall his mates as he

leads his fellow servicemen along St. George's Terrace on the ANZAC

Day march. "I look forward to the annual reunion, of meeting

old friends, and seeing who is left," he said. "I might not be

able to make it next year."