Navy Victoria

Network

Proudly supported by the Melbourne Naval Committee

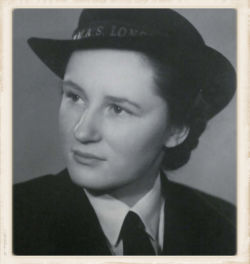

LWRWTR Edith Jessie FLANDERS (nee Edgar), WR/1528

Edith

Jessie Flanders was born on the 10 March 1921 and grew up on her

father’s property 7 miles out of Harrow, Victoria. Her mother

did not have a licence and as she could not travel to school, she

was educated by Governesses until she went to boarding school at age

14.

Edith

Jessie Flanders was born on the 10 March 1921 and grew up on her

father’s property 7 miles out of Harrow, Victoria. Her mother

did not have a licence and as she could not travel to school, she

was educated by Governesses until she went to boarding school at age

14.

Jessie's story below, by Sue Smethurst, first appeared in the Australian Women's Weekly on 25h March 2019.

At 98, Jessie Flanders can finally tell her family that, in World War II, she was a code cracker and a spy.

As dawn broke over Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance on Anzac Day 2018, war veterans gathered along St Kilda Road readying themselves for the annual march, their enthusiastic camaraderie warming the crisp, solemn autumn air. Among these revered men and women who served our nation with valour was Jessie Flanders, who at 97 was marching in the Melbourne service for the very first time.

On Jessie’s lapel, almost outshining her proud smile, was a precious gold pin she’d received from former UK Prime Minister David Cameron. The veteran Women’s Royal Australian Navy officer was taken by surprise when the little package, postmarked from England, arrived at the post office of her home town Casterton, in far western Victoria, seven years earlier.

“I wondered who on earth would be sending me something all the way from Britain,” she says. Accompanying the pin was a certificate which read, “Deepest gratitude on behalf of the British Government for the vital service performed during World War II”.

Bletchley Park commemorative badge

On the reverse side is engraved 'We Also Served'

It was the first time that her role in the war effort had ever been formally acknowledged and it was a signal that Jessie could at last share the very big secret she’d held dear for decades. Jessie’s friends and family believed she had worked in a secretarial role for the Navy during the war. In fact, Jessie was a spy and she played a pivotal role in helping the Allies win WWII.

“We were absolutely sworn to secrecy and told that we mustn’t tell anyone, not even our parents, what we were doing. So I did what I was told and I kept mine sealed,” she says. “My mother and father died not knowing what I’d done during the war. Even my late husband didn’t know and I’m a little bit sad about that, but that’s how it was. We were sworn to secrecy and I kept my word.”

It’s only now that the story of Jessie Flanders and the remarkable women on the top-secret Special Intelligence Bureau is beginning to emerge. From a secret Melbourne base, codenamed “Monterey”, an outstation of the famous Bletchley Park operation in England, Jessie and a team of highly skilled women secretly intercepted the radio instructions of Japanese commanders, decoded them and relayed the enemy battle plans to Allied command. They are credited with saving hundreds of Australian sailors.

"MONTEREY" Apartments

17 Queens Rd, South Yarra, Melbourne

Housed the Special Intelligence Bureau (RAN)

The Directorate of Naval Communications (RAN)

and the Analytical Section of FRUMEL (USN/RAN)

(FRUMEL - Fleet Radio Unit Melbourne)

“When I felt it was okay to talk about, I told my children and they said, ‘Mum, you were a spy!’ Thankfully they were impressed and not horrified!”

Melbourne at war

Jessie Flanders, or Jessie Edgar as she was known back then, was just 18 years old when Hitler invaded Poland and the world went to war. Jessie, who was in her last term of boarding school in Melbourne, wanted to help out and begged her parents to allow her to stay in the city and get a job, rather than returning to the family farm near the tiny township of Harrow in far western Victoria.

They agreed on the condition that her sister live with her. Armed with a sense of false bravado and determination not to return to the farm, the two country girls marched into the offices of the Shell Corporation and secured clerical jobs. They were among the first women employed by Shell in Australia.

The Shell building happened to be next door to The Blue Triangle servicemen’s club, so Jessie and her colleagues would visit the soldiers on respite and volunteer their time serving meals or playing cards with the troops.

At the time, the impact of war was beginning to be felt at home and Melbourne was vulnerable to attack. The government enforced nightly brownouts, with every home hanging thick black curtains to block light that might attract Japanese bombers; trenches were dug through the pristine parks and gardens, and any buildings that had solid basements were made to turn their underground space into air raid shelters. Street lights were dimmed, cars drove with hooded lights so they couldn’t be seen and search lights were used to detect enemy aircraft.

War had well and truly arrived in Melbourne and the mood on the street was tense. “It was terribly frightening,” Jessie says. “I felt a little bit helpless at Shell, I wanted to do more to assist the war effort.”

Jessie, encouraged by the soldiers she’d been helping, decided to join the navy. “My friend Mary and I signed up and were sent to Point Lonsdale base for training. After two weeks, we got uniforms and vaccinations and we were told we were being posted to Monterey. Of course, we had no idea what that was or what we would be doing; we just did what we were told. We volunteered to go anywhere, we didn’t mind. Sadly, women weren’t allowed to travel overseas then but we were prepared to go anywhere we were needed.”

The women who cracked codes

They found themselves close to home in a block of flats in Queens Road, St Kilda. On the outside it looked like a regular apartment building, but inside the apartments had been converted by American forces into a series of secret decoding rooms.

The only hint that something out of the norm was going on there was the armed American guards checking the girls’ identification as they came and went for their shifts. They worked around the clock in small teams, intercepting messages between Japanese command. They would translate the messages from Japanese and decode them, then alert Allied command to the Japanese plans.

Jessie became familiar with Japanese language, particularly as it

related to the military, and “if a convoy was going to be attacked

or a place was going to be bombed, we could alert the precise

division so they could change course or amend their plans. Now that

I’m telling the story, I realise how significant it was but at the time

none of us understood it – we were too busy cracking codes. I now

know that we saved a lot of lives.”

Jessie became familiar with Japanese language, particularly as it

related to the military, and “if a convoy was going to be attacked

or a place was going to be bombed, we could alert the precise

division so they could change course or amend their plans. Now that

I’m telling the story, I realise how significant it was but at the time

none of us understood it – we were too busy cracking codes. I now

know that we saved a lot of lives.”

The Monterey Unit operated between 1942 and October 1944, and is

now widely credited with playing a significant role in the Allied

victories in the Pacific. Monterey assisted in the Battle of

Midway in 1942, the destruction of a Japanese convoy of more than

5000 army reinforcements and the death of Japanese Admiral Yamamoto,

which proved a devastating blow to Japanese morale. Almost all

of the 80-strong team who worked in rotating shifts at Monterey were

women.

“On our very first day there, we had to swear on the Bible we wouldn’t tell another soul what we were doing – not our families, no one, ever.

We wondered what it was all about at first, but we pretty quickly realised that what we were doing was important. “It was quite a buzz when you intercepted something you knew was important – we’d rush the message to command who would fully decipher it and work out what was going on. We knew the importance of time. If we missed an important code, sailors would die.

“I distinctly recall one night when I deciphered a code which

said ‘attack’. I ran as fast as I could into the command office and

told them the Japanese were going to attack an Allied convoy sailing

up the east coast of Borneo. The message was instructing the

Japanese ships where to rendezvous and at what time so they could

attack our ships, but we managed to alert our officers and they

changed course in time. We felt very happy about that – we

definitely saved lives that night and it felt really good to have

contributed to something so significant.”

“I distinctly recall one night when I deciphered a code which

said ‘attack’. I ran as fast as I could into the command office and

told them the Japanese were going to attack an Allied convoy sailing

up the east coast of Borneo. The message was instructing the

Japanese ships where to rendezvous and at what time so they could

attack our ships, but we managed to alert our officers and they

changed course in time. We felt very happy about that – we

definitely saved lives that night and it felt really good to have

contributed to something so significant.”

Jessie still remembers the day peace was declared as if it was yesterday.

She was working the evening shift when word came through that a treaty had been reached.

“Oh, the celebration, it was marvellous. The streets went wild but I was at work so I missed most of it, and when I finished my shift the guards escorted me home. It was wonderful but it also meant we were out of a job. Monterey was shut down very quickly and that was it, we were discharged from the navy.”

After three years in the navy, Jessie went back to the farm for a break, intending to have some time off and then return to Melbourne to find a new job. But in the meantime she fell for the charms of a returned fighter pilot, Bob Patterson, and the pair married. They made their home at Warrock Homestead and built a thriving sheep station, one of the most revered in Victoria. Jessie and Bob had three children, Robert, Richard and Annie, and they lived happily on the farm until Bob died in 1975, aged just 54. Jessie never revealed to Bob what her role in the war had been and it was only decades later that she began to share her extraordinary history with family.

Warrock Homestead

“When we were growing up in the 1950s, everyone around us had their war stories,” recalls Jessie’s son Richard. When we asked Mum what she did in the war, she would reply, ‘I was just a driver in the navy’. Only many years later did we discover that her role was a significant one and one that seemed quite unbelievable. She has many skills and one of her greatest is maths. It is wonderful that she was able to use this in the decoding work she did at Monterey, but it’s a shame that she was unable to share her experiences with anyone. She is certainly very good at keeping secrets!”

After Bob’s death, Jessie moved into nearby Casterton, which has been home ever since. She married a family friend, John Flanders, and they lived happily together until his death in 2000. Jessie has remained actively involved in the community and is a treasured resident of the tiny Casterton township. Her name is also inscribed on the Harrow war memorial as a living hero.

Despite community recognition and the thanks of the British government, Jessie and her Monterey colleagues have never been formally recognised by any Australian authorities for their role in the war.

“The British pin was wonderful and I am very honoured but this was sent out 50 years after the war and sadly now many of the women I served alongside have passed away, which is a great shame, that they never received the credit they deserved. It would be nice for those women to be recognised.”

The Australian Women’s Weekly has contacted the Department of Veterans’ Affairs on Jessie’s behalf to see if this can be rectified. The service woman, formally known as WRAN E.J. Edgar, WR1528, Leading Writer, hopes that she will celebrate her 98th birthday by again marching in the Melbourne Dawn Service with granddaughters Emma, 34, and Samantha, 31.

“I think the stories of women in war are really only beginning to

surface,” Jessie says, “and I do feel it’s important that we keep

the stories alive and honour the women who are no longer here. I’ll

do whatever I can, while ever I can. War is terrible and we must

always remember that.”

NOTE: As a follow-up to the above

article, Sue Smethurst is currently working on a book about the role

this group of Australian women from Monterey played code-breaking

during World War 2, as they are now credited with saving the lives

of many Australian and Allied sailors and soldiers in the Pacific.

COVID-19

Herald-Sun journalist Mandy Squires interviewed

Jessie in March 2020 about isolating during covid-19.

Former navy decoder Jess Flanders, 99, who still lives independently in her Casterton home, is also self-isolating to keep herself and family members safe.

She has a new great-great grandchild and another soon to arrive but won’t be able to visit either of them.

“But that’s OK — there’s nothing we can do about it. Lucky we have the telephone and I’ve just learnt how to use Facebook so I can see the baby photographs,” Mrs Flanders said.

Although she lived through rationing of petrol, clothes and food in Melbourne during wartime, Mrs Flanders said today’s conditions with the rapid spread of coronavirus were certainly frightening, but she hoped they would not drag on.

“It’s not going to last forever and if we do the right thing and stay at home and don’t mix with other people, and do all the other things they’ve asked us to do, we might get this nasty virus under control … I guess we just need to hang in,” she said.

Mrs Flanders, who lost her first husband to a blood disease resulting from his time as a bomber pilot during the war, said she felt sorry for people who had lost their jobs due to COVID-19, “because most were just good honest, hardworking people who had their heads above water … and now it’s all gone”.

Edith Jessie Flanders - Author - her historical novel "His Own Man" was published in 2011.

Edith Jessie Flanders has taken a small but important oral history that explains a significant part of the story of the much loved working dog, the Australian Kelpie, and placed it in context by researching the life of an Irish immigrant family.

Her research about the Irish potato famine and the related transportation and assisted migration to the colonies, about the highs and lows of trying to make a new beginning in a harsh environment and about the ways that families had to come to terms with the new ways and new social order in their adopted land makes for lively and entertaining reading.

His Own Man follows the family and the lurking curse that they find difficult to shake. The story spans three generations to fully explain the actions and motives of young Jack Gleeson, a good lad but one who was faced with temptations.

This is a story of men and women and their modest but heroic efforts as they pass through the convict system, the gold rushes and the difficulties of life in the Western District of Victoria.

The author's research, the oral history provided by her father-in-law, her many years of living in the area and her deep understanding of life on the land enable her to write a convincing historical novel that has been read with enthusiasm by many people.

source: Kelpie Publishing

ABC Western Victoria by Sue Dunstan

The town of Casterton in south-west Victoria is recognised as the birthplace of the Kelpie and the story of how the bloodline was created and spread throughout the country has made its way into folklore.

Casterton woman Jess Flanders has used a mixture of oral history, research and a bit of conjecture to write a book that is part history, part novel.

Jess Flanders explained about her very personal connection with the Kelpie story and the blending of fact with fiction in her book "His Own Man".

VALE Edith Jessie Flanders (nee Edgar)

On the 14th August 2020,

Jessie passed away peacefully in her sleep. She was 99.

Coincidently her passing was on the eve of the 75th anniversary of Victory

in the Pacific day.

Lest We Forget.

Interview with Jessie Flanders in 2019

This is one ladies story and she is “The Last Decoder of

Monterey”. Monterey, home

to a secret Royal Australian Navy intelligence unit called FRUMEL

during World War II.

Footnote: The above video

is titled "The Last

Decoder of Monterey". We're not sure if Jessie was

the last Code Breaker and

we are currently investigating if there are any WRANS from Monterey

still alive today.

Sources:

Sue

Smethurst

Geerlings Digital Moments

Herald-Sun

ABC - Sue Dunstan