Navy Victoria

Network

Proudly supported by the Melbourne Naval Committee

CDRE John Malet ARMSTRONG CBE DSO US Navy Cross

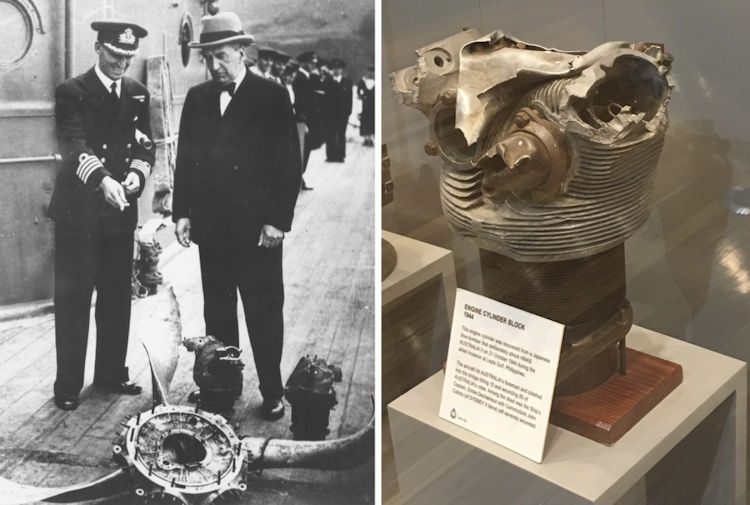

He was made a Midshipman on 1 January 1918 and joined HMAS Australia (I) at Scapa Flow, Scotland, in April. Described as intelligent and tactful, and shy yet energetic, his successive Commanding Officers in Australia all saw promise in Armstrong. Captain Oliver Backhouse, CB, RN, commented on 31 August 1918 that he was "Intelligent, keen and hardworking...a zealous, intelligent and promising officer". On 31 December 1918, Captain Thomas James, RN, described him as "Very conscientious in all his duties. Has the making of a very good officer". Captain Claude Cumberlege, RN, on 19 November 1919 described him as "A very keen and promising officer". Back in Australia after the war, he joined the crew of HMAS Brisbane (I) on 18 September 1919 and was promoted to Sub Lieutenant the following month and Lieutenant on 15 March 1921. He underwent a series of courses in Britain specialising in gunnery in the early 1920s and on 7 July 1924 married Philippa Suzanne Marett at St Brelade on the Channel Island of Jersey. He returned to Australia in October 1925 to be posted to HMAS Cerberus and in 1927 he was the Navy's guard commander for the opening of Parliament House in Canberra. He served in HMA Ships Adelaide (I) and Sydney (I), and upon Sydney's decommissioning in May 1928, served for two years on exchange with the Royal Navy. He was promoted to Lieutenant Commander on 15 March 1929 while serving in HMS Castor on the China Station. Lieutenant Commander Armstrong returned to Australia in March 1930 and served in HMAS Australia (II) before taking on a number of staff appointments ashore. He was promoted to Commander on 30 June 1935 and undertook another two year exchange posting with the Royal Navy from July 1936. He commanded HMS Broke from July 1937 to January 1938 before taking passage back to Australia. He returned to the Royal Australian Naval College, which had moved once again to Flinders Naval Depot in Victoria, as Executive Officer between March 1938 and July 1939. Armstrong, known as ‘Jamie’ to his fellow officers, and nicknamed ‘Black Jack’ by the sailors, was back serving in HMAS Australia (II) as Executive Officer at the outbreak of World War II. Australia (II), commanded by Captain Robert Stewart RN, was involved in patrol and escort work in the Indian Ocean in the early months of the war, and in July and September 1940 conducted operations against Vichy French forces at Dakar. In October 1940 Australia was searching for a suspected raider in the North Atlantic when a Sunderland Flying Boat came down in heavy seas north of the Hebrides in one of the worst Atlantic gales of the year. After the ditched aircraft commenced sending out weak wireless distress signals, Australia at 8 a.m. on October 29th was ordered to search for the disabled Aircraft. Captain Stewart and the Navigator, Commander J. Payment, R.A.N. (who died of wounds at Leyte four years later while still serving as Navigating Officer of the Australia) set a zig-zag search pattern course in a Force 8 gale. At first the cruiser pitched and rolled through the seas at 26 knots, but as the weather worsened speed had to be reduced. So severe was the gale that the forecastle was damaged and water leaked below decks. In those early War days Australia was not fitted with radar. Visibility was only two to three miles, and extra lookouts were employed to search for any sign of the Sunderland. The flying boat was not in the position it had estimated but Australia located it by ‘homing’ in on the faint signals the aircraft was sending out from time to time. At 2.20 p.m. the Sunderland transmitted ‘Hurry up, cracking up’. Captain Stewart knew he was getting close. The ship made puffs of smoke, and a searchlight beam was swept across the bearing on which it was expected to sight the flying boat. At 2.35 p.m. the Sunderland was sighted 2 miles ahead on the port bow, firing rockets and flashing ‘Hurry’ by Aldis lantern. As the cruiser approached, the flying boat capsized. For a time two of the airmen clung to the sinking aircraft’s upturned keel and the rest bobbed about in the raging, freezing sea. Captain Stewart manoeuvred his ship close to the airmen. Australia’s upper deck amidships was normally about 28 feet above the water line. However, with the roll of the ship and the state of the seas, at times the troughs of the waves were over 36 feet below the upper deck level. Over eight feet of hull and barnacle coated anti-torpedo bulges and bilge keel were exposed which could take a man to his death as the ship rolled. Commander ‘Black Jack’ Armstrong, with a dozen of the ‘Aussie’s’ crew in bowlines, went over the side into the boiling North Atlantic sea in the icy water. One by one they had to be hauled on board, With the ship rolling heavily, the airmen’s heavy water-logged gear made for a long and difficult task. Persistence and sheer bravery from those over the side securing each airman finally triumphed. Nine of the crew of thirteen were finally on board, suffering from exposure, but they would be safe after time spent in the sick bay. The nine rescued were Flight Lieutenant Giddy, Pilot Officers Evans and Neugebauer, Sergeants Gough, Taylor and Cusworth, L.A.C. Gay and Mechanics Hicks and Bond. Midshipmen ‘Red’ Merson (later Commodore J.L.W. Merson, R.A.N.) recalled that the nine were practically helpless with cold and the effect of sea water. The remaining four of the crew drifted out of reach past the Australia. "I can still recall the utter frustration of seamen trying to reach this group with heaving lines, but the wind force made it totally impossible to cast a line – it merely blew back in one's face before achieving its objective – to reach the doomed four." LCDR (then Midn) Mackenzie Gregory - Oct 1, 2017 Captain Stewart reported in his War Diary that the remaining four were either swept under the ship or along the ship’s side. He saw two or three bodies to windward but then they disappeared. He got under way to place the ship in a position where it would drift down on them, but sadly the remaining four airmen were never seen again. At 5.25 p.m. after over two hours, the hopeless search for survivors in U-boat infested waters was reluctantly abandoned. All they were to have would be 60°:50′ North, 11°:35′ West as their Atlantic grave. In gloomy darkness, with the weather worsening to a full gale and rough seas of over 30 feet in height, the cruiser headed south for its base at Greenock, Scotland. As they recovered, the rescued crew from 204 Squadron’s Sunderland K/204 (P9620) gave a graphic account of how a severe magnetic storm had put their compass and wireless out of action. The aircraft became hopelessly lost, and after over twelve hours in the air ran out of fuel and came down in the very rough Atlantic Ocean. The wireless operator, after a great deal of trouble, was able to send out signals but was unable to receive them. During the ten hours in the sea, as the Sunderland tossed about at the mercy of the mountainous waves, the airmen suffered severely from sea sickness. In 1941 ‘for outstanding zeal and devotion to duty’ Armstrong was Mentioned in Despatches, ‘while serving in HMAS Australia’. He was made Acting Captain on 30 April 1942 and commanded the armed merchant cruisers HMA Ships Manoora (I) and Westralia (I) during the year. At the time of his substantive promotion to Captain on 31 December 1942, he was Chief of Staff to the Flag Officer in Charge (FOIC) Sydney, and became Naval Officer in Charge (NOIC) New Guinea in November 1943. In October 1944 he was appointed Captain of his old and favourite ship Australia, eight days after a kamikaze attack had claimed the life of her Commanding Officer, Captain Emile Dechaineux, DSC, RAN, along with six other officers and 23 ratings. He was in command in January 1945 when Australia (II) covered the allied invasion of Luzon Island at Lingayen Gulf. He gained a reputation for coolness and bravery when his ship was subjected to repeated suicide attacks and was hit on 5, 6, 8 and 9 January, losing three officers and 41 ratings killed and one officer and 68 ratings wounded. ‘As he stood on the for’d end of the exposed open bridge the Skipper didn’t turn a hair,’ recalled the then Navigator, Commander Jack Mesley. On January 9, 1945, Admiral Oldendorf, United States Navy, sent this signal to HMAS Australia. ‘Your gallant conduct has been an inspiration to all of us.’ Captain Armstrong wrote a personal letter to each of the next-of-kin of the 44 men killed in action. The following is one such example: (A copy of Captain Armstrong’s letter to the mother of 20-year-old A.B. Alan Lade by courtesy of his cousin Jean and David Hopkins.) HMAS Australia, C/o G.P.O.

This was the ship’s last action in World War II. After repairs in Sydney, Australia (II) sailed for the United Kingdom, via the United States, on 24 May 1945 for a major refit, arriving at Plymouth on 1 July. As Australia approached the English coast a flight of Sunderland Flying Boats from No.10 Squadron operating from Coastal Command’s base at Mountbatten flew low past the 17-year-old veteran with 14 World War II battle honours, dipping their wings in salute as they passed and then escorted the ‘Aussie’ into Plymouth Sound. Coastal Command’s way of paying tribute to the 1940 rescue of their Sunderland crew. In July 1945 Captain Armstrong with 13 of the crew of the Australia received their decorations at an investiture at Buckingham Palace by King George VI, and the Ship’s company marched through the bomb scarred streets of London. Captain Armstrong was awarded the D.S.O. for: ‘gallantry, skill and devotion to duty at Lingayen Gulf’. The United States of America awarded him the Navy Cross. This citation read: ‘for distinguishing himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity in action during the capture of Lingayen Gulf in 1945. Although his ship was heavily hit suffering heavy casualties and the disablement of a large portion of her anti-aircraft guns and radar system. Captain Armstrong maintained his assigned station and the Australia carried out her bombardment missions.’ Armstrong relinquished command of the cruiser on 5 August 1945. Before leaving he gave a farewell address to the 'Aussie’s’ crew. There were tears in this eyes as he said 'Goodbye you pack of bastards'. He then left for the Pacific to take command of the Escort Carrier H.M.S. Ruler, followed by H.M.S. Vindex. This was so that he could gain experience in carriers. It was planned he would be appointed Commanding Officer of the R.A.N’s first postwar carrier.

On return to Australia he was appointed Second Naval Member of the Naval Board on 3 April 1946 with the rank of Acting Commodore 2nd Class, a promotion which was confirmed on 24 July 1950. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire on 7 June 1951. Armstrong had been selected as Captain of the RAN’s first aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney (III); however, a broken arm, which took an unusually long time to heal due to a previous break in the same spot, precluded him from taking up the command. Ongoing problems with the injury combined with his failing eyesight meant that he was declared unfit-for-sea in July 1951. Armstrong continued to hold staff appointments in Australia, Britain and the USA, his final appointment being as Australia’s first Defence Research and Development Representative in Washington DC. He retired on 14 August 1958. Known as 'Jock' from childhood and as 'Jamie' by his wife and his fellow naval officers, Armstrong was described by the Bulletin in 1954 as 'inevitably "Black Jack" to all hands, from hair, cliffy eyebrows and a dark general weathering burned-in over 40 years of naval service'. He was a good-looking man, standing six feet (183 cm) tall with a nose broken when playing Rugby. Armstrong had many friends and was able to move in all circles. He was dedicated to the naval profession and fearless under fire. Typical of many successful naval officers of the time, he preferred activity and practicality over staff work, which was his distinct weakness. A modest, humane and devoted family man, he took a progressive attitude to training, believing young naval officers to be poorly educated, too isolated and over-supervised and disciplined. In retirement, Armstrong moved to Jersey in the Channel Islands with his wife, Philippa, where he trained the Jersey Sea Scouts, fished, tended his gardens and joined the Imperial Service Club and the Naval and Military Club, London. He passed away on 30 December 1988 in his home at La Haule, and his ashes were buried in the Marett family grave in the cemetery of the parish church at St Brelade, Jersey. He was survived by his wife, two sons and a daughter. Sources:

|

John

Malet Armstrong was born on 5 January 1900 in Sydney, the

son of Dr William George and Elizabeth Jane Armstrong.

He was educated at Sydney Grammar School and All Saints

College in Bathurst, NSW, before entering the Royal

Australian Naval College in 1914, at that time located at

Osborne House in Geelong, Victoria. He was

successively made Cadet-Captain and Chief Cadet-Captain, and

won his colours for rugby and swimming.

John

Malet Armstrong was born on 5 January 1900 in Sydney, the

son of Dr William George and Elizabeth Jane Armstrong.

He was educated at Sydney Grammar School and All Saints

College in Bathurst, NSW, before entering the Royal

Australian Naval College in 1914, at that time located at

Osborne House in Geelong, Victoria. He was

successively made Cadet-Captain and Chief Cadet-Captain, and

won his colours for rugby and swimming.